In a previous essay, I said:

Something I was reminded of while watching the third, most famous movie version of The Maltese Falcon: the works to remake in one’s own image aren’t the classics but the almost-classics, the works whose central conceit was much better than the final product. Singular, perfect works are hard to improve on but there are lots of books and films sabotaged by their creator’s shortcomings and the commercial realities of the day. If anyone wants an essay on “books I wish someone would use as a springboard for executions that are actually good,” just ask.

People did ask, so here we are.

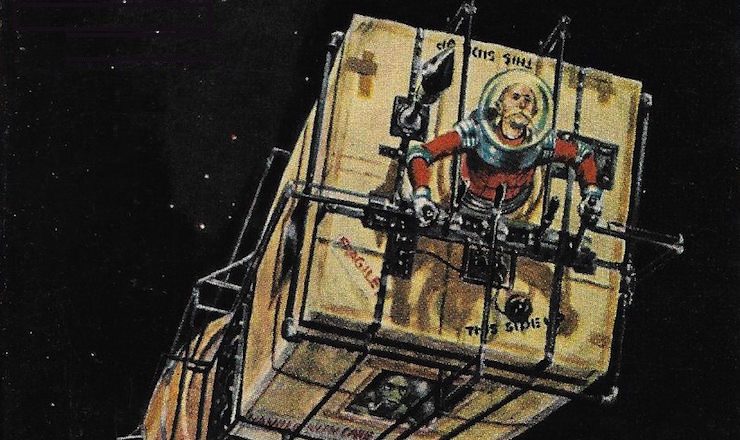

Fred Pohl and Jack Williamson’s The Starchild Trilogy is one of the series that made me think of the idea in the first place. It’s full of wonderfully zany ideas, from an entire ecosystem fuelled by living fusion reactors out in deepest space to living stars willing to share their mentality with billions of people. What’s not to like?

The actual stories themselves, as it turns out. Unsurprisingly for a veteran writer whose career began in the jazz age, Williamson’s fiction was firmly rooted in the pulp era. Co-writer Pohl seemed happy to follow his elder’s lead. Having created this delightful backdrop, the pair then told perfectly conventional tales about heavy-handed dictatorships with ambitions of total rule and mad scientists bent on creating stars in their hidden laboratories1.

Poul Anderson’s The Makeshift Rocket may have had its roots in Anderson’s desire to sell something to John W. Campbell (who was all too fond of stories featuring handwavium-based reactionless space drives). Anderson may also have been thinking of Jack Williamson’s SeeTee novels when he created a world in which the gyrogravitic generator gave anyone with enough money the ability to reach and terraform an asteroid. What a setting! There are almost a million asteroids more than a kilometre in diameter in the asteroid belt (twenty five million if all you want is a Little Prince-sized estate). All of them could be home to a pocket nation. That would be more worlds than many galactic empires.

Anderson touches on the potential of his setting, but the story he tells is a rather tiresome comic retelling of the Fenian Raids2, one based on the notion that ethnic stereotypes are funny, as are the daffy girls who insist on tagging along with the guys’ adventure. There is so much potential here. Anderson leaves most of it on the table.

Which brings me to Jerry Pournelle’s “Those Pesky Belters and Their Torchships“3, the lone non-fiction entry in this essay. This 1974 piece poked a bit of fun at authors like Larry Niven, whose gravity-well-shy Belters zoomed around on overpowered rockets apparently unaware that saving 11 km/s getting off planets is a hollow savings if you routinely expend thousands of km/s travelling from one orbit to another. Pournelle points out the plot-rich potential of settings with more modest propulsion, which still allows for an asteroid belt with many polities rather than one. It also allows for gas-giant moon systems to form polities.

The essay is also an outlier in that I think it accomplishes pretty much what it could do with the information then available, in the word count available. I mention it here because I object to how little influence that essay has had over the following decades. Michael Flynn’s The Wreck of the River of Stars was definitely influenced by the essay and M.J. Locke’s Up Against It might have been (at least, it is a plausible example of the sort of book someone drawing on the essay might produce) but where are the others?

And then there’s Asimov’s Foundation. Now, my inclusion of this may surprise some of you. After all, the original trilogy won a Hugo for Best All-Time Series in 1966 and Foundation’s Edge won a Best Novel Hugo in 1983. It’s not that the series has not been a success. It’s that Asimov decided to make his Space-Rome the only power in the galaxy. If the Galactic Empire had been more faithfully modeled on historical Rome, then it would have been one of several major powers. Where are the analogs to China and Persia, to the Gupta Empire, to Kadamba and Axum? To the Eastern Roman Empire?

It’s not as if a galaxy more closely modeled on the real-life 5th century CE world would have derailed Asimov’s decline and recovery plot. The 5th century was in general a dismal time to be a great empire in the Old World—if it wasn’t waves of Central Asian barbarians threatening invasion, it was climate-changing volcanoes and/or plague. Rome had company in its decline; the Gupta Empire and Persia were sorely pressed by invaders, while the Liu Song Dynasty replaced the Eastern Jin dynasty. So why can’t a series drawing on Old World history reflect its delightful complexity?

If you are lucky, you are either too young or too not-Canadian to have been exposed to my next candidate, the venerable television show The Starlost. Based on a premise by Harlan Ellison, The Starlost was set on a generation ship whose inhabitants had forgotten they were on a ship and who certainly didn’t know it was headed for a star. The program should have been entertaining. What it was, in actuality, was the sort of poorly written, ineptly produced, badly acted sci-fi hackwork that really highlights the potential benefits of macular degeneration. In response to the cuts and changes to his original concept and story, Ellison had his name removed from the credits and is listed under the pseudonym “Cordwainer Bird.” There’s nothing wrong with the basic premise, though, as a multitude of novels from Orphans of the Sky to Captive Universe prove. Even better is the fact that even a bad remake would still almost certainly be superior to the original.

This is yet another list dominated by works by men. I suspect this is because the bar tends to be higher for women authors. Consequently, they don’t tend to produce lazy works flawed in the specific ways needed to trigger my “write something like this but good” reflex.

That said, there is a woman-dominated genre that makes me yearn for a different version. I will use as my example Kelley Armstrong’s Otherworld series, specifically the lyncanthropic Smurfette Elena Michaels books.

Some day I’d love to read about werewolves whose behavior is based on that of actual wolves. Failing that, it would be nice if the supernatural beings weren’t murder gangs convinced that their special powers give them license to kill any who inconvenience them. Also, if domestic abuse were treated as, well, domestic abuse and not courtship.

Except….

Someone did write the werewolf books for which I was yearning: Carrie Vaughn. Her Kitty Norville series features a woman protagonist whose values are firmly modern, Abusive behavior on the part of her local pack turns out to be not an essential element of lycanthropy, but a reflection of the fact that her local pack is primarily composed of bullies and jerks. Sometimes it turns out the series one wants to read has already been written.

1: Creating stars in laboratories on the very planets you inhabit turns out to be a bad idea.

2: The Fenian Raids were a 19th century attempt by Irish nationalists to steal Canada so they could then blackmail Britain into granting Irish independence. That may seem an excessively audacious proposal but to quote my review of The Makeshift Rocket, “it failed by a lot less than you would expect from ‘rag-tag rebels attempt to heist an entire god-damned country.’”

3: Writers looking for an ambitious expansion of Pournelle’s essay might want to look at Winchell D. Chung Jr.’s exemplary Atomic Rockets.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.